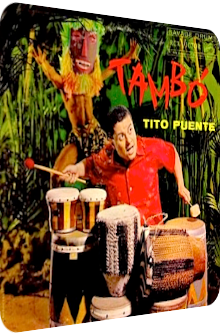

Tito Puente

Tambó

1960

The old metaphorical imagery of the king of the jungle is a traditional depiction, it has been used to death and is now not much more than an empty alloy for a once meaningful and strong vividness. I use it nonetheless when talking about timbalist and drummer Ernesto Antonio “Tito” Puente (1923–2000) and his twelve-track Exotica milestone Tambó. Recorded on two consecutive days in April 1960 at the Webster Hall in New York and released in the same year on RCA Victor, the album takes the drum escapades of my all-time percussion favorite Top Percussion (1957) and revs up its raw ritualistic essence with sound elements that otherwise belong to concrete jungles. Flutes, mallet instruments and a large amount of horns are stacked onto the jungular sceneries, but they feel much more tropical than de trop and are so consequentially in the spotlight and epicenter that they are no antimatter at all.

Produced by drum expert Marty Gold, known for his exquisite sparkler Skin Tight (1960), Tambó expresses the vivid imagination of Tito Puente, as ten compositions are written by him, with another one being submitted by the band’s pianist Gilbert Lopez, followed by one single rendition. The personnel comprises of bandleader, bongo player and timbalist Tito Puente, bassist Roberto Rodriguez, dedicated bongo players José Mangual Sr. and Louis Pérez, congueros Carlos Valdez and Ray Barretto as well as timbalist Ana Correro. These drummers are accompanied by additional players too numerous to mention them all – among them eight brass experts – but a lasting impression is delivered by flutists Alberto Socarras and Rafael Palau, as this exotic ingredient bolsters the jungle thicket decidedly. Afro-Cuban Jazz with an exotic and decidedly adventurous angle: here comes Tambó.

Proto-Exotica, mercilessly banging, even most portentous a procession: enter the Dance Of The Headhunters, a brutish reticulation of timbale galores, bursting bongos, callisthenic congas, and in the center of it all, erupting horns whose fanfare-like euphony grows as the literal drum rolls proceed, shuttling between off-key incisiveness and glorious overtones. The wideness of this opener is breathtaking, the echoes, reverb and hazy afterglow magnificently absorbable. This is a cinematic masterpiece. New York stops shaking and trembling when pianist Gilbert Lopez’s own Call Of The Jungle Birds is presented: a verdured piece of carefree jungle tropicana in 6/8 time, Seymour Berger’s trombone and Alberto Socarras’ warbled Polynesian fife erect an aural rain forest that is further brought to life by triangles, plinking timbales and Lopez’s gentle piano undercurrent. A strong earwig with its own peculiar flavor, Call Of The Jungle Birds is another success.

Whereas Rumba-Timbales presents a tachycardia of Tartarean dimensions with murderous drum infestations and various textural intertwinements followed by a stumbling appendix, The Ceremony Of Tambó brings back the piercing abrasion of the horns, now in show tune form amid a fusillade of ultrafast bongos and timbales. Despite the breakneck speed and dangerous tunnel vision, the playfulness of the brass melodies prevents this song from being interpreted as a savage tribulation and towers all the more above the treetops. The follow-up Velorio is a Haitian rendition of John Conquet’s eponymous composition with a more laid-back and saccharine flavor. Rhythm pianos and the shrill polyphony of the flutes are the trademark. Naturally, the drums are not silent either and return full force on Cuero Pelao, an adamantly repetitive drum-only arrangement of vitreous timbales and bongo backdrops.

Jungle Holiday opens side B in a superbly green style. A hypnotic marimba leitmotif holds together the expected bongo-and-conga couples, but also twirls and gyres in such a mesmerizing way that a feeling of bliss is growing with every second. Socarras’ flute flumes augment the purity of this jungle vista, and even though the kaleidoscopic nature becomes warped and spacy at the end, the pristine innocence is what the traveler takes away in his heart when experiencing this stellar piece. Guaguancó meanwhile places golden Honky Tonk piano chords in an eminently argentine kettle drum and timbale influx whose churning frequencies are, at least in hindsight, prophetically industrial, with the consecutive Ritual Drum Dance improving its orderly rhythm with different bongo patterns and various pauses that let the listener fathom the depth of the panorama; histrionic horn gales round off the cinemascope before the inner eye.

Witch Doctor’s Nightmare follows, but no worry, this is the only instance of a cheeky comic relief ditty. Rafael Palau’s saxophone is comparably dusky, but the two-note scheme of the glockenspiel and trombone sounds sun-soaked and benign. This is more oneiric than nightmarish. The penultimate Son Montuno moves into a different kind of exotic feat: Cha Cha Cha. This already diaphanous Latin style is further brightened up by Santos Colon’s guiro-driven rhythm, Gilbert Lopez’s amicable six-note rivulets on the piano and the echoey decay of the drums. This is also the song where bassist Roberto Rodriguez is allowed to connect the parts and build bridges with short solo segues of double bass goodness. His presence continues to be noticeable in the glorious finale Voodoo Dance At Midnight, a multilayered brass-interspersed drum gigantomachy with one-note horns of Jericho and chlorotic greeneries. Grapevine leafs of the mind.

There is a reason why Tambó is one of Tito Puente’s biggest albums, a chart-topping success for a smasher of an album that ususally resides far away from such a place near the sun. I still prefer Puente’s Top Percussion and its stupefyingly green color range – its deep red front artwork notwithstanding – but can definitely see, accept and all the more embrace the genius behind Tambó: by adding pianos, flutes, mallet instruments and throning brass instruments, the album caters to a vast audience, including people who are a more than a tad intimidated in the wake of a drum-only album. Even though the principal textural base is the same for, on and in each composition, the vast amount of different instruments offers enough variety despite the basic premise of a drum-focused LP. Arrangement-wise, there is enough room for several melodies to shine, even though some of them are mere vestiges. Highlights include the magnificent opener Dance Of The Headhunters with its gleaming, almost seething trumpets, saxophones and trombones, Jungle Holiday with its mellow marimba mélange and the flute-oriented Call Of The Jungle Birds.

These are – coincidentally or not – three particularly melodious takes of a more than wondrous roster, but make no mistake, there is more to the album than these frilly hymns. And at the same time, there is more to it than heavily scything drum patterns. The truth, as I see it, is found in the middle. Yes, it is a boring truth, equilibration is a double-edged sword. It is thus all the better that Tambó does not keep the balance on a per-song basis rather than on the album as a whole. Each song is indeed focused on the task at hand, be it shapeshifting rhythms, ridiculously fast drum dioramas or, yes, even the much needed and tastefully realized doldrums on a lazy afternoon in the jungle. If the listener encountered Tambó before 1957’s Top Percussion and wants to bask in (almost exclusively) drum-driven coppices, the predecessor is the better choice. Luckily, this is an academic recommendation, as both albums are ultimately worth it. Especially Tambó should be owned and worshipped by the Exotica fan. It is available on vinyl, and remastered CD versions as well as digital incarnations.

Exotica Review 337: Tito Puente – Tambo (1960). Originally published on May 3, 2014 at AmbientExotica.com.